Bacteria. They are an amazing life form. There are about 5 million trillion trillion on the planet. They can reproduce fast – one species multiplies so fast that a single cell can become a billion cells in 5 hours. They can survive in the most inhospitable of climates (one species thrives in 400’C underwater thermal vents, and scientists have revived bacteria from 100,000 year old ice). By comparison, the canine bladder is cosy and comfortable – which is bad news for us and our dogs, especially Tilly.

Tilly in hospital

What happens?

When bacteria grow in the canine bladder, the bladder can become inflamed (inflammation of the bladder is called cystitis); increasing blood flow to the bladder and flooding the area with infection-fighting cells and supportive chemicals, which can cause swelling and discomfort. This can cause the sensation of a full bladder, which leads dogs to strain in an attempt to empty a bladder that doesn’t need emptying. Straining causes more swelling, which causes more straining and so on, until the bladder is so bruised that it bleeds.

The bacteria causing Tilly’s bladder infections were able to change the chemical nature of her urine, altering both pH (or acidity) and mineral content. Unfortunately, this caused the excess minerals to solidify into crystals, like salt on your arms after swimming at the beach. In time, the crystals became stones, which rattled around doing even more damage and making it harder to control the infections.

What will I see?

As an owner or carer, you might see; an unhappy dog with a hunched-up appearance and frequent trips to urinate, straining, discoloured urine, or even blood clots. To complicate matters, you might see these or similar symptoms for other reasons too. And cystitis can be caused by things other than infection. But they’re topics for another day.

What will the vet do?

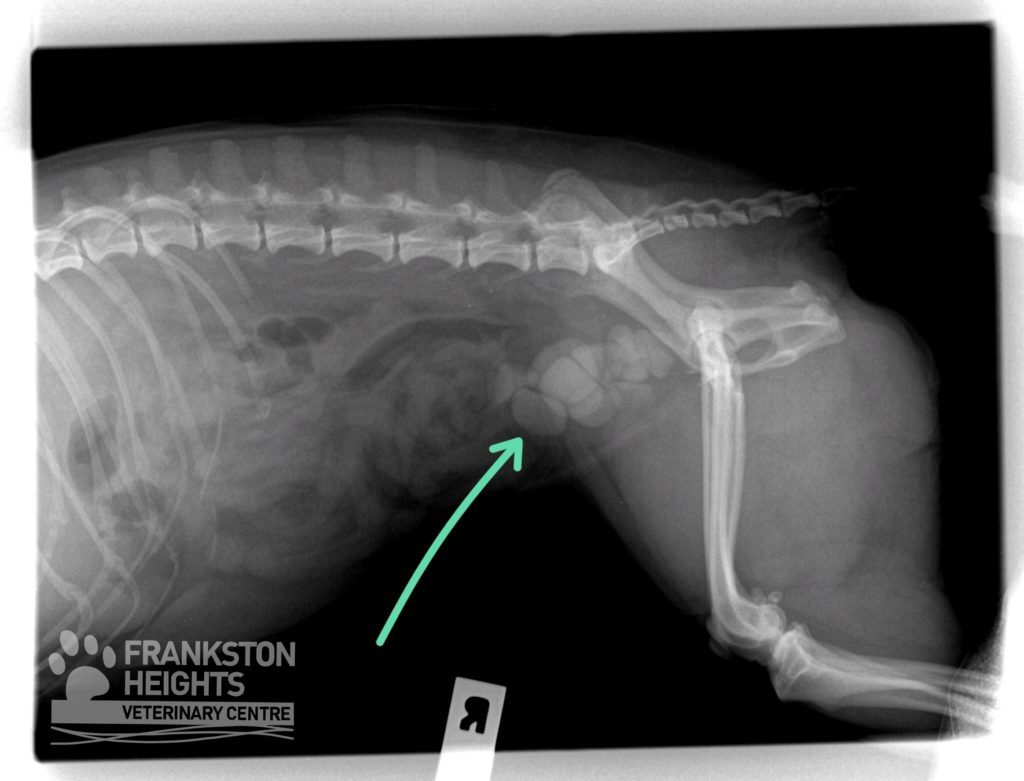

Examination of urine is a vital part of investigating cystitis; being a vet isn’t always as glamorous as it sounds! Not all cystitis is caused by infection, so we assess the chemical make-up of the urine, and also use a microscope to look for blood, bacteria and crystals. With severe (or reoccuring) cystitis, we may need to ultrasound or xray the bladder, to look for stones or other changes to the bladder. Tilly’s stones showed up nicely on xray.

Tilly’s xray

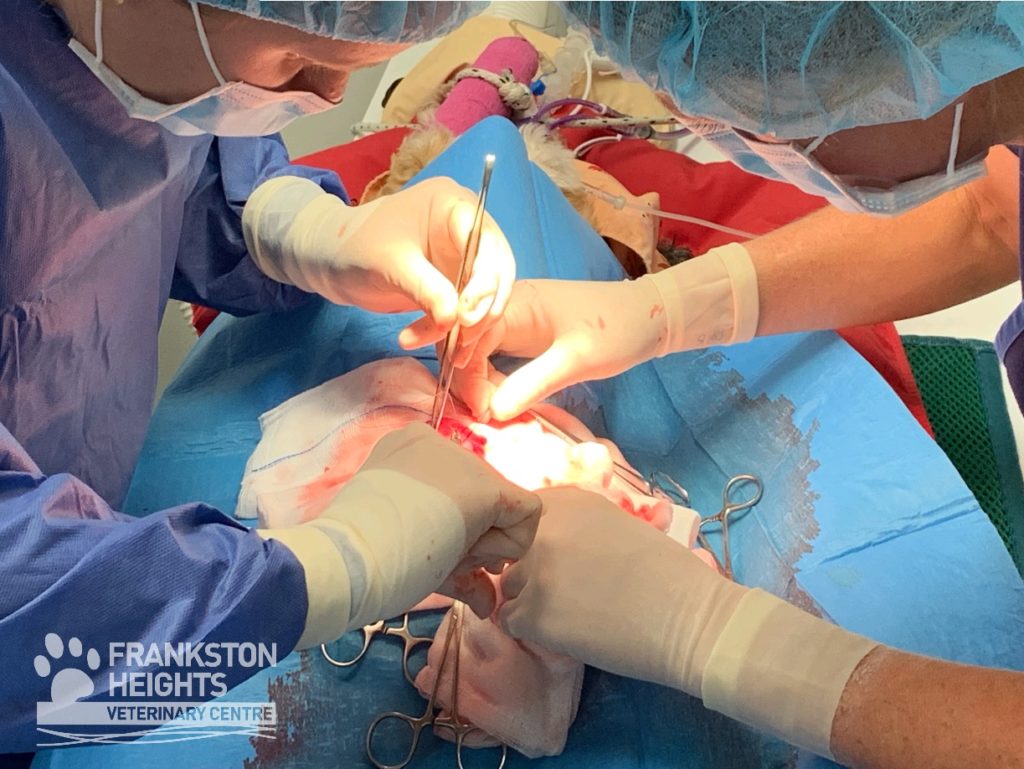

Cystitis is uncomfortable, so often the first job is to take pain away. If there is infection, we may need to use antibiotics. Sometimes we use a specific food to make it harder for the crystals or stones to form. Unfortunately, once stones are present in the canine bladder, an operation is usually needed to remove them. The good news is that this operation can be done by Dr Isabella and the surgical team, right here at Frankston Heights Veterinary Centre. Once removed, we send the stones to be analysed, and can then we put a prevention programme in place to try and stop them forming again.

Dr Isabella and Dr Martika operating on Tilly

Till’s bladder stones

As always, the first step is to watch your dog and learn what they do normally; then you’re more likely to recognise when something isn’t quite right. And if you’re worried; call us – it’s what we’re here for!

Oh, and Tilly went home wagging her tail. She had her stitches removed this week, and is now happy and weeing comfortably!

References – Discover Magazine | BBC Earth | Nature – International Journal of Science